Women’s History Month: Celebrating the women of our cemeteries

- 15 March 2023

Women’s History Month

March is Women’s History Month, and in celebration we are taking the time this month to acknowledge the histories of some of the Australian women whose achievements advanced the rights and visibility of women in the city of Melbourne, and who are now taking their eternal rest in our cemeteries.

These three selected women greatly influenced the spheres of the arts, science, women’s rights, sports and cultural life in our city. By looking back at the innovative women of the past, we can use their successes and their places in history to help us envision what women’s rights and gender equality looks like to us in 2023 and beyond.

Ada Cambridge (21 November 1844 – 19 July 1926), Brighton General Cemetery

Ada Cambridge was a poet and author who became one of the defining voices of turn-of-the-century Australian writing. Born in Norfolk, England, Cambridge had been writing poems since her teens and published some early works on religious themes by her early 20s. In 1870, she wed George Frederick Cross, a curate who was about to embark on colonial service, and the couple landed in Melbourne in August of the same year.

Her husband’s pastoral work took Ada to many parishes across Victoria, including Wangaratta, Yackandandah, Ballan, Coleraine, Bendigo, Beechworth and finally Williamstown. Cambridge initially threw herself into the work of being a mother and clergyman’s wife, but after a period of ill health she turned back to writing as a means to help support the family.

Her first novel with an Australian focus, Up the Murray, was serialised in the Australasian in 1875, and the publication of A Marked Man in 1890, which followed the fortunes of two generations grappling with radical and conservative conventions in colonial Australia, propelled Cambridge into the leagues of the nation’s most popular writers. She did however face sexist criticism: her focus on women and familial themes put her at odds with the prevailing literary style at the time of men battling with the extremes of the landscape, and some critics felt that some of the daring ideas expressed in her novels, such as extramarital affairs and the inequality women faced in the institution of marriage, were too unseemly for a clergyman’s wife.

Cambridge passed away in 1926 in Elsternwick. Her legacy includes the ‘Adas’, a suite of poetry, short story, and biographical prose prizes presented each year by the Williamstown Literary Festival, a fitting tribute to the seaside suburb’s most famed literary daughter.

Lady Janet Clarke (4 June 1851 – 28 April 1909), Melbourne General Cemetery

Lady Janet Marion Clarke was a philanthropist and socialite who balanced a glittering public life with arts patronage, charitable works particularly focusing on women’s rights and suffrage, and played a foundational role in the creation of Australian cricket’s greatest prize.

Born at a station on the Goulburn River, Clarke became a governess to the children of Sir William Clarke and later married him in 1873 after the death of his first wife. She became a society hostess at their East Melbourne mansion Cliveden, and at their Sunbury property Rupertswood. It was at Rupertswood where the Clarkes hosted the English cricket team for Christmas in 1882 after they had played three Test matches against Australia. In a cheeky gesture, given the English had lost, Lady Clarke presented England captain Ivo Bligh with a small urn containing some burned ashes, likely of a cricket bail. This became the Ashes urn, now one of cricket’s most iconic trophies.

Clarke’s philanthropy was largely focused on women and people experiencing poverty. During the depression of the 1890s she ran a soup kitchen out of Cliveden. She was a member or president of a truly astounding array of charitable, cultural and public service organisations, including the Women’s Hospital Committee, the Alliance Française, the Charity Organisation Society and helped to establish the College of Domestic Economy. The Victorian branch of the National Council for Women was founded in 1902 to consolidate a number of women’s rights organisations and Clarke became its first president. She was also the president of the Women’s National League, which was a conservative political organisation devoted to educating and assisting women in voting in elections.

On the day of Lady Clarke’s funeral and burial, among the mourners following her cortege from St Paul’s Cathedral to Melbourne General Cemetery were some fifty of Melbourne’s newsboys, of whose society Lady Clarke had been president, and many students from the University of Melbourne’s Trinity College who had benefitted from a donation from Clarke that resulted in the building in 1889 of the Hostel for Women University Students, which was later renamed Janet Clarke Hall and today is its own college.

Fannie Eleanor Williams (4 July 1884 – 16 June 1963), Springvale Botanical Cemetery

Fannie Eleanor Williams, professionally known as Eleanor Williams, was a groundbreaking scientist who specialised in bacteriology and serology and co-founded Australia’s first blood bank.

Born in Adelaide in 1884, Williams trained as a nurse at Adelaide Children’s Hospital. Very soon after the completion of her training she was appointed sister in charge of the Thomas Elder Laboratory, where she worked as an assistant to pathologist Dr Thomas Borthwick. She followed Dr Borthwick when she took up an invitation to join him at the new pathology research laboratory at Adelaide Hospital, where she became the first woman in South Australia to work as a laboratory attendant.

At the breaking of WWI Williams received another invitation to go overseas with the First Australian Imperial Force in Egypt. The Australian forces had been greatly afflicted by infectious diseases, particularly dysentery. Working alongside Dr Charles James Martin, Director of the Lister Institute, Williams performed ground-breaking work throughout the war, quickly becoming an expert in infectious diseases and became the only Australian woman to serve in the war specifically as a bacteriologist.

On her repatriation Williams moved to Melbourne and took up a position at the newly founded Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (now known as WEHI), becoming the third employee and first woman appointed. She would go on to work the rest of her career at WEHI, where she continued specialising in infectious diseases and serology, and expanded her expertise into snake venom research. Along with Dr Ian Wood she co-founded Australia’s first blood bank in 1939, establishing new techniques to store blood and use it for transfusions. She co-wrote numerous research papers and was one of the first Australian women to be published in a medical journal.

Her role at WEHI was not easily defined – Williams performed duties that combined those of a research scientist, senior laboratory technician who had her own laboratory and trained all new lab assistants, and a general manager. She had no university qualification, nor was she a medical doctor, which, combined with her position as a woman, allowed her contributions to be diminished in comparison to her male contemporaries. Her influence on those contemporaries and all who came through her laboratory, however, was immense: she was remembered by Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, first one of her trainees and later director of WEHI, as “the centre of commonsense and helpfulness around which all the activities of the Institute rotated.”

As a good scientist Williams always seems to have preferred to be a collaborator first and foremost, yet she was undoubtably a leader, instituting high standards and paving the way for women in science with her own quiet, yet highly impressive excellence.

Recommended articles

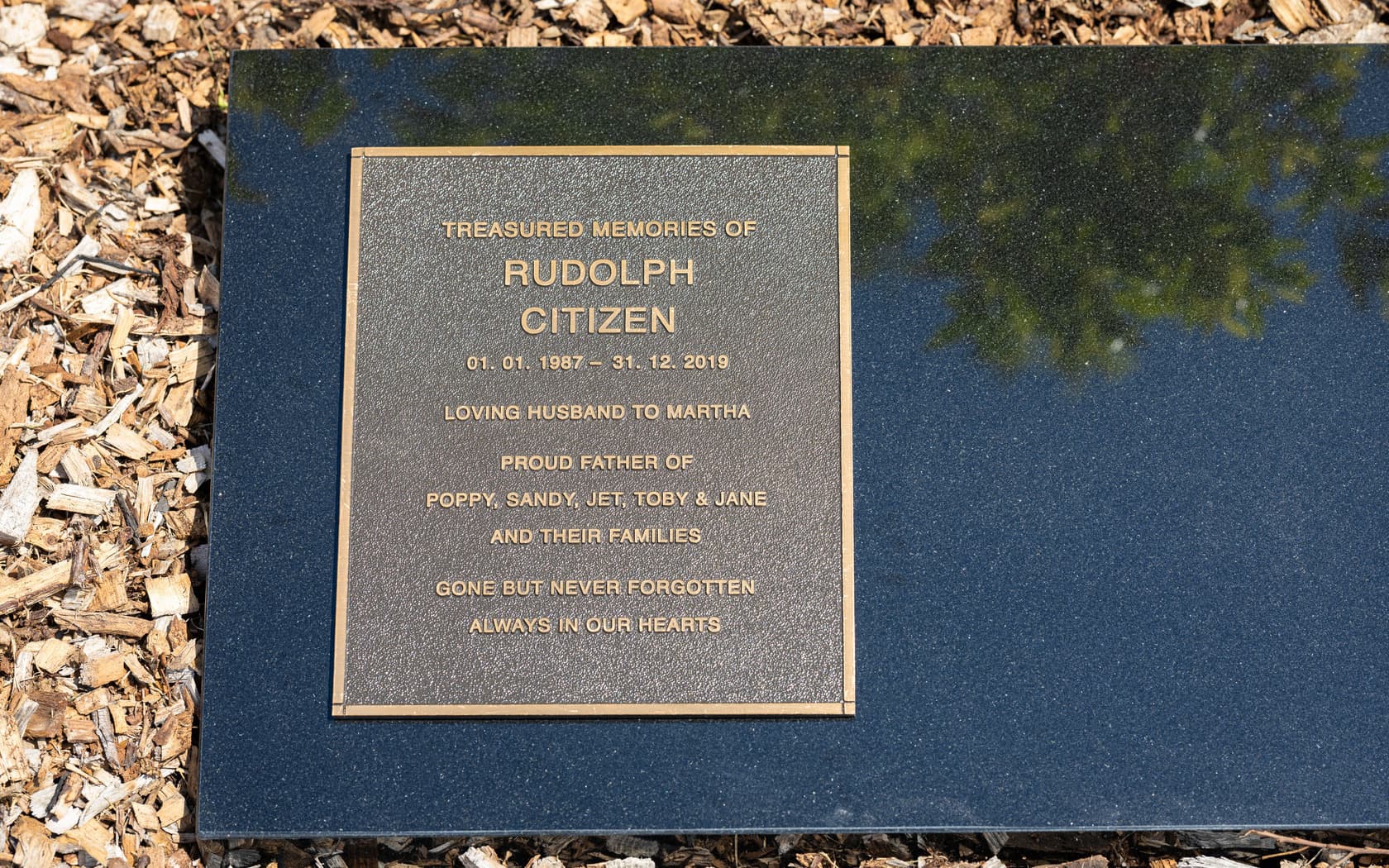

How to clean and maintain a bronze plaque

Regular plaque maintenance helps slow gradual aging and protect the plaque’s original beauty for many years.

Easing grief through planning: Supporting families before, during and after loss

Discover how SMCT supports grief and end-of-life planning in Melbourne. Learn about MyLifeBook, the Community, Care & Wellbeing program, and how planning ahead can ease emotional and financial stress for families.

How to create the perfect memorial plaque

Discover how to create a meaningful and lasting memorial plaque with this step-by-step guide. Learn about messages, design tips, and trusted resources from SMCT.